The Tariff Math That Could, And More Likely Will, Empty Shelves

Upstream costs means downstream problems

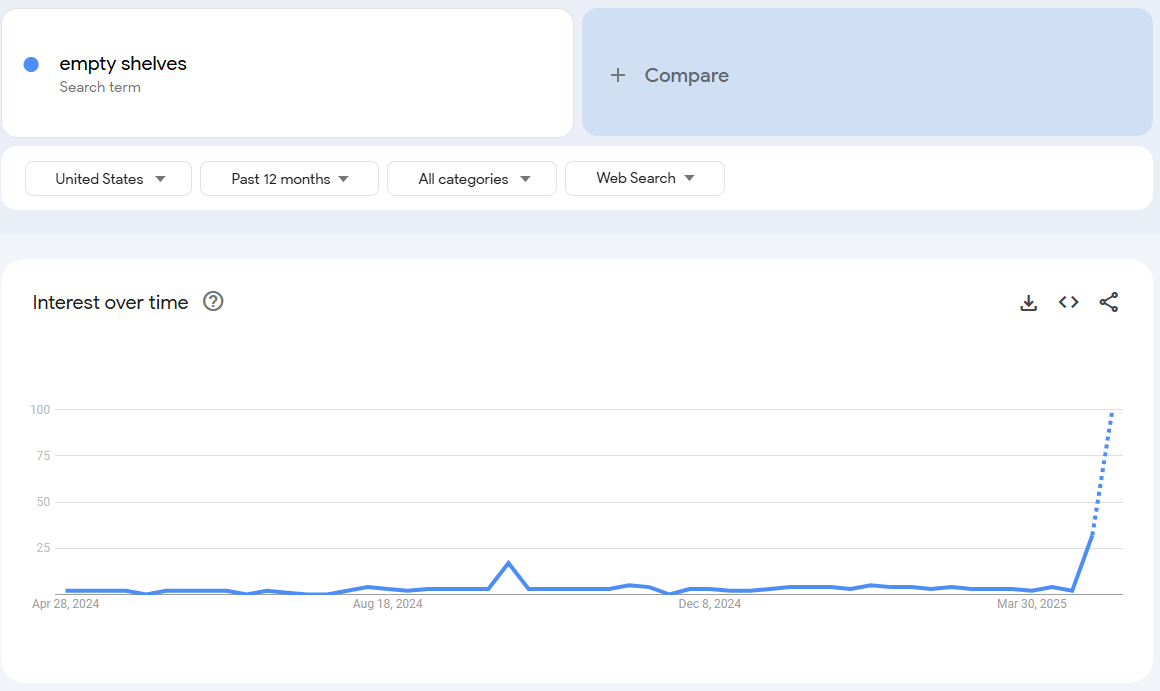

Since Donald Trump declared Liberation Day almost three weeks ago, there have been non-stop stories about the tariff rates being assessed to our trading partners. The biggest headline by far is the 145% tariff being placed on goods from China (at least as of this writing). Combined with upcoming May 2nd repeal of the de minimis exception, everything from household appliances to cheap clothing from Shein and Temu will be subject to the same import rules. Many businesses have started to sound the alarm that they will be unable to import at all with tariffs at these levels. Below is a quick sample of articles warning about potential shortages and Google Trends results for "empty shelves."

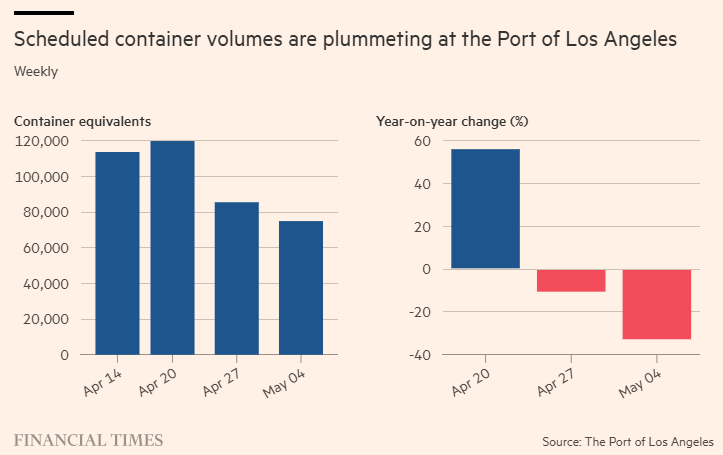

While Apple reportedly flew several planes full of iPhones to bolster inventory before tariffs fully kick in, most businesses have to rely on ocean freight to get their bulk inventory from China. That journey across the Pacific takes anywhere from 15-30 days depending on the ports in question, and that transit time has briefly delayed what's now clearly coming. In the last few weeks, business reporters and people that follow international shipping have started posting about a forthcoming cliff in inbound shipping to the US.

This more recent from the Financial Times shows the drop off quite clearly.

Based on the year-over-year trend, companies have clearly pulled shipments forward, but after April 20th, that's over and done with. If, and more likely when inbound shipping craters, the next domino to fall will be the commercial trucking and rail companies that get merchandise moved across the country. Less inbound containers means less work for those haulers. All of this impacts what is on store shelves, and as we'll get into shortly, what price is being charged for those items. Some specific product categories might see less impact, but we imported almost $440B in 2024 and finding new manufacturing partners takes time. A lot of time. Unlike the early days of the pandemic, the product shortages we are likely to see now are entirely self-inflicted and the logic for why that will happen is actually very straightforward.

Simple Math

A tariff is a fee assessed on items when they are brought into the country. This applies to raw materials and finished goods alike. Most importantly for purposes of understanding the direct impact on business, is the fact that they are paid upfront.

While Silicon Valley software companies tend to get all the media buzz, this country still buys and sells a lot of STUFF. As a business, selling physical products means spending money a lot of money upfront to get those items manufactured and shipped on the hope that you can eventually sell them, get cash, and do it all again. If you're able to sell those items profitably, you can scale and grow your operations over time.

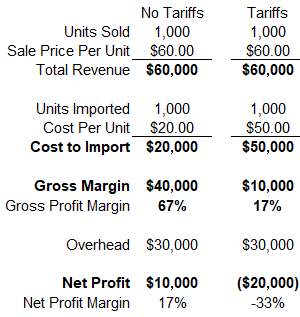

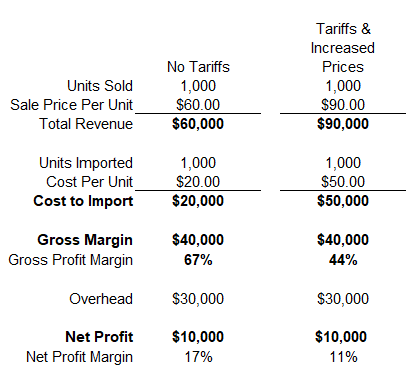

Let's imagine a clothing company operating in normal times. They design their items here in the United States but use a manufacturer in China. Keeping things as simple as possible, let's also assume they only sell shirts and that in a non-tariffed scenario getting them manufactured and shipped to the U.S. costs $20 per item. They then turn around and sell those shirts for $60, netting $40 in margin per item sold. That sounds great until you remember that that margin has to pay for everything else the business needs to run: the employees, the office and warehouse, utilities, marketing, etc. Every business selling physical products depends on a relatively consistent, or at least predictable, cycle of inventory coming in and being sold. Big disruptions to that cycle are what put companies out of business. If they see that certain items aren't moving as fast as they'd like, they can offer discounts to clear the inventory since it is better to make a reduced margin and try again than having capital trapped in products that aren't selling at all. Owners set their prices to make the big math problem hopefully result in a profit at the end. All of this of course is before the impact of tariffs that drastically change that calculus.

For sake of ease, we'll round up the 145% tariff on Chinese goods to 150%. As soon as the tariffs kick in, getting product into the country now means our imaginary company has to pay $50 per item instead of $20. This means that getting 1,000 shirts into the country now costs $50,000 instead of $20,000. If they don't raise prices on new inventory this erases 75% of their margin overnight ($10 vs $40). This is a double whammy because committing the extra capital to bring in more inventory puts pressure on every other part of the business that needs cash. Here is a quick illustration of the math above:

Assuming our imaginary business changes nothing, the amount of money they make on newly imported inventory won't cover their overhead costs (people, rent, marketing, etc.) and they will post a loss. The example above is precisely why anyone who is being honest about tariffs will tell you that they will ultimately have to be paid by the customer. Business owners have no choice but to pass those costs on and are still taking a huge risk to bring in the inventory in the first place. In the example below, the $30 increase in unit cost has been 100% passed through to the sale price.

From the imaginary business owner's perspective, if they were still able to sell the same amount of shirts in the usual amount of time even after raising prices, then great. But unfortunately, that isn't how most customers will respond. Consumers grow accustomed to paying certain prices for certain things. Outside of the very wealthy, a 50% price increase on anything that isn't a necessity is probably going to mean no purchase at all and then things fall apart quickly.

So What Happens Now?

Bluntly stated, if these tariffs stay in place then wide swaths of products that American consumers are accustomed to buying will become either unavailable or priced higher than many are willing to pay. The administration has stated that they want to use the tariffs to encourage domestic manufacturing, but building capacity equivalent to what we are shutting off in imports would take years and still can't solve for the labor cost differential that drove the factories abroad in the first place.

Don't just take it from me. Here is an excerpt from an article at Ars Technica on how the China tariffs will impact board game manufacturers. This is just one industry, but it speaks to the broader problem.

Most US board games are made in China, though Germany (the home of modern hobby board gaming) also has manufacturing facilities. While printed content, such as card games, can be manufactured in the US, it's far harder to find anyone who can make intricate board pieces like bespoke wooden bits and custom dice. And if you can, the price is often astronomical. "I recall getting quoted a cost of $10 for just a standard empty box from a company in the US that specializes in making boxes," Stegmaier noted—though a complete game can be produced and boxed in China for that same amount.

Meredith Placko is the CEO of Steve Jackson Games, which produces titles like Munchkin, and she had a similar take. "Some people ask, 'Why not manufacture in the US?' I wish we could," she wrote in a post yesterday. "But the infrastructure to support full-scale boardgame production—specialty dice making, die-cutting, custom plastic and wood components—doesn't meaningfully exist here yet. I've gotten quotes. I've talked to factories. Even when the willingness is there, the equipment, labor, and timelines simply aren't."

That last comment is really the most critical. The expertise to build certain kinds of products at scale simply does not exist anywhere but in China. One can criticize how we got here all they like but it doesn't change the fact that in the immediate near term all these tariffs will do is raise prices and make some items functionally unobtainable for vast numbers of American consumers. For small businesses that rely on China for inventory manufacturing these tariffs are existential and could mean having to shut down or massively downsize once their current pre-tariff inventories are sold through. In closing, I feel obligated to repeat that damage this will cause is entirely self-inflicted and was done with a sledgehammer.

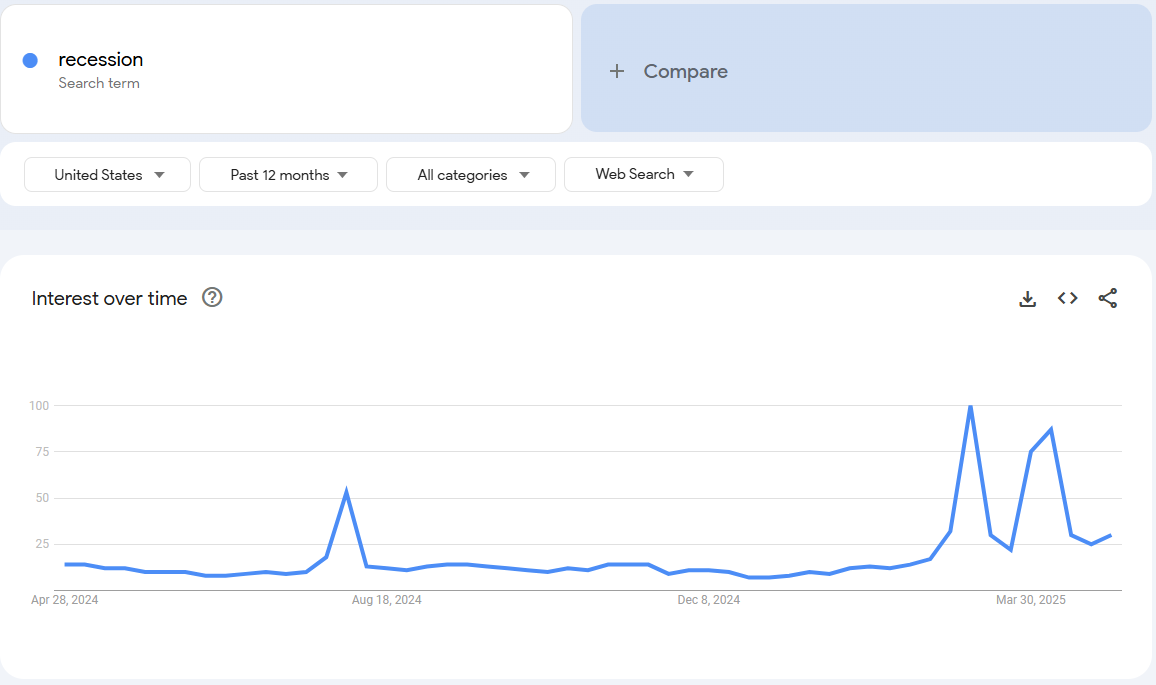

I don't know where we go from here, but recession talk is in the air.

If you liked this piece and aren't already, please consider subscribing. Share with a friend. Also please remember that I am a team of one, so any typos are fun and on purpose!